- News and Stories

- Blog post

- Safety Net

Following the User Need Beyond Traditional Boundaries

In 2018, Code for America began exploring whether and how technology and user-centered design might improve the way government helps more people find and keep living wage jobs. Notably, our team did not include workforce experts. We brought a fresh perspective, and relied on our engagement with users and experts to better understand the many opportunities and challenges in the workforce ecosystem. Re-envisioning the complex workforce ecosystem requires courageous policymakers, activated constituents, creative advocates, innovative government servants, and many more to think outside the confines of the status quo to create the conditions for economic stability and opportunity for all. We hope that sharing the story of our workforce discovery process will support the ongoing efforts of the many dedicated individuals and organizations working to improve the public workforce system for those who need it most.

Over the course of nine months, our workforce team engaged over 200 system stakeholders (leaders and frontline staff) across 16 states, and conducted interviews with 75 people seeking training, employment, and other services from workforce development agencies. We worked to identify and understand the user need and the system, identifying the key pain points for clients seeking services and for government service providers. Based on these pain points, we conducted a series of short discovery sprints to deepen our understanding of root causes, system challenges, and opportunities to eliminate or reduce the impact of these pain points on workforce clients. We created nineteen paper and digital prototypes and used them to engage with clients and system leaders in search of solutions. Our work confirmed what many in the field already know to be true: the workforce system is not meeting the needs of the people who need it most.

But it does not need to be this way. At Code for America, we believe that government can provide workforce services that center the needs of constituents, are responsive to the changing economy, and leverage community resources to help people find and keep jobs that pay a living wage. Below we share our key insights around why the current system struggles to meet client needs, as well as key opportunity areas where we believe technology and user-centered design could help make this vision of workforce services a reality.

Key Insights about the Workforce System

1. The workforce system was not designed as a system; it is a complex ecosystem with high variance in service delivery.

The workforce system is deeply fragmented, both in funding and in delivery. Job seekers who turn to the government for workforce development services find themselves navigating a labyrinth of possible service agencies from community colleges, American Job Centers, training providers, rehabilitation programs, employer programs, and nonprofits. Our attempts to map this complex ecosystem revealed that although there are some similarities nationally, each individual workforce context has its own unique structure, set of stakeholders, funding mechanisms, opportunities, and challenges. Workforce stakeholders should be incentivized to bring the larger ecosystem into greater alignment around priorities and metrics, which will help facilitate the creation of technology solutions that support job seekers and provide government with the user insights and feedback loops necessary to inform operations and policy.

This is not a system, it was built as separate universes. There have been no incentives for any of these systems to work together—policies trying to do so are unfunded mandates. So it is not a ‘re-architecting’ issue; this is rebuilding from the ground up.

2. Training alone will not lead to living-wage jobs for all. We need to raise the floor and build ladders.

In the current economy, most workers can find a low-wage job. But we need to set a higher bar. It is not beneficial to our communities for workers to have to work several jobs to simply make ends meet. It is incredibly difficult for a person with only a high school diploma to find a job that pays enough to support and sustain a family. With the rise of automation and the gig economy, and the reduced power of unions in many states, most analysts expect job quality to continue to decrease unless strong action is taken. In order to help more people find and keep living wage jobs, we must build the foundation that supports people in work and improve conditions for all workers. We must raise the floor. And, we must build ladders that support clients on their career journey through more affordable training opportunities. This requires many workforce agencies to shift their priorities, and to think more broadly about what steps we can collectively take to turn more jobs into living wage jobs.

Not all jobs will be automated, but many of the jobs that are likely to stay are currently very low-wage, low-quality jobs. How do we invest in those non-automatable jobs becoming living wage, quality jobs?

3. Employment barriers, poor working conditions, and the benefits cliff keep job seekers trapped in poverty.

Employment barriers—such as lack of transportation and childcare, a criminal record, or mental or physical health issues—can trap low-wage workers in a cycle of poverty. Low wage workers often live on a knife’s edge, where the smallest crisis can cause them to lose their jobs. We heard stories from workforce clients around the reasons they weren’t able to retain jobs, such as unreliable public transportation or missing a few days of work to care for a sick family member. We also heard about how a stressful or inappropriate situation at work, like forced overtime or discrimination, caused workers to leave their jobs to the detriment of their careers. Clients often get trapped in a cycle: receiving workforce services, moving into entry-level jobs, losing or leaving those jobs, returning to workforce supports, and repeat. To advance to quality jobs that they find meaningful, workers need to be able to stay in jobs long enough to build skills and position themselves for the next step in their career.

I have a history of applying for jobs I don’t really want out of desperation, and taking them out of desperation, and getting frustrated, ya know, hanging on by my fingernails until I just can’t stand it anymore.

To make matters worse, if workers begin to overcome these barriers, the current benefits system tends to punish progress, rather than reward it. Low-wage workers who are starting to get ahead may risk the loss of crucial benefits if they take small pay increases or increase their hours at work. To clients, this “benefits cliff” can make it feel nearly impossible to break out of poverty.

I can only work about 25 hours a week before I make too much and they cut my son’s health care—he has autism so I really need it. So I can’t take on more hours, even though I know that’s what I need to do to get the job I want as a manager.

4. The workforce ecosystem is collecting a lot of data, but much of it is not being used in meaningful ways.

Despite spending a huge amount of energy tracking data for compliance, workforce leaders often cannot tell you basic information about who is using which services, and are even less likely to have data-informed insights into which programs are successful at helping people find and keep living wage jobs. As a result, workforce agencies, employers, and educational institutions are rarely aligned on which training programs lead to jobs, or how to help people get the skills needed for the jobs of the future. In part, this is because the workforce ecosystem is often focused on the wrong outcomes. Without effective metrics, one state leader in charge of apprenticeships noted, “making decisions on budget feels a little like trial and error.”

Even when the right information is being tracked, it can’t be leveraged for decisionmaking unless it is put into the hands of the people who need it, at the right time, in an understandable format. To create the feedback loops needed to get better results in the workforce ecosystem, workforce stakeholders must come together to identify which outcomes are most important to clients, and build the systems to allow them to track and share these outcomes with decisionmakers at all levels.

Opportunity Areas for Technology and Design in the Workforce System

Our conversations with clients and workforce leaders across the country surfaced a core set of pain points—these were user and system needs that we heard repeatedly in our conversations. We translated these pain points into opportunity areas by asking key “how might we…” questions, and we identified success criteria to help us evaluate potential solutions where government could play a role in addressing each of these pain points. .

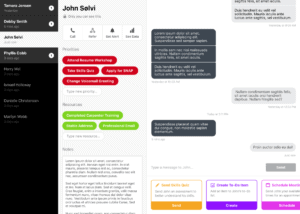

Next, we began a series of discovery sprints that helped us engage leaders and clients around potential solutions. Because we had a broad range of issues to explore and limited time, we used a series of short discovery sprints (2–4 weeks) that allowed us to maximize learning by quickly testing various ways of addressing each pain point. We would select an area to focus on for a few weeks, reach out to users most impacted by that pain point in order to understand it more deeply, ideate, and prototype potential solutions. We used these prototypes to spark generative conversations with users and system stakeholders.

After a few weeks of focus it felt like we were just scratching the surface; there were always great people to collaborate with and ways we felt we could make a difference. In the end, it was this discipline—forcing ourselves to move on to the next sprint, continuing to follow the user need wherever it took us—that allowed us to find the biggest opportunity to have an impact.

What follows are several opportunity areas that we identified through these sprints to help job seekers find and keep living wage jobs.

1. Wrap Around Services

How might the workforce system more effectively help job seekers address barriers to employment, such as lack of transportation, food access, housing, healthcare, childcare needs, or a criminal record?

In order to successfully participate in training, find a job, and keep a job, job seekers cannot be in crisis. Wrap-around services can help clients meet basic needs so that they can fully participate in workforce programs. Some workforce programs have comprehensive wrap-around services for participants, at times even including on-site housing. These are effective programs because they provide participants with the level of stability required to be able to participate fully in education and workforce activities without major distractions. The majority of workforce programs make referrals to outside service providers, but case managers often do not have the capacity to follow up with clients to know whether the referrals actually helped the job seeker access the support that they needed. And we learned even with high-quality case management and improved referral systems through tech and design, if there aren’t sufficient resources on the other end of that referral, our work would have limited impact.

Despite these challenges, there is a lot of potential for improvement in this area. Some of the solutions we identified have the potential to be scaled nationally. For example, we learned that we could build tools to help clients gain access to well-paying jobs in ports across the country by providing more in-depth support for accessing the Transportation Worker Identification Credential. We also learned that we could help people access the Earned Income Tax Credit through digital services, which is ultimately what we believed to be our highest impact opportunity.

2. Access to Paid Job Training

How might the workforce system increase job-seeker’s access to paid training opportunities?

Job seekers and low-wage workers typically have immediate financial needs and cannot afford to forgo income to participate in an unpaid training program. Our user research reinforced the need for “earn and learn” or paid training opportunities that would allow workers to advance in their careers while maintaining their monthly income. There are a number of models for paid training, such as incumbent worker programs, paid internships, transitional employment, participation stipends, apprenticeships, and more.

Technology and design could help identify nontraditional sectors that could benefit from apprenticeships, support more equitable access to existing paid training opportunities, help businesses collaborate to create apprenticeship programs, and improve the experience for participants.

3. Outcomes Accountability

How might the workforce system improve feedback loops to ensure that limited resources are used most effectively?

The workforce system lacks sufficient information about key job seeker outcomes. This is true despite the fact that the different parts of the workforce system collect a significant amount of data as part of their regular course of work. As a result, workforce leaders make decisions without relevant data, and they are incentivized to invest in the wrong things. At the same time, job seekers have to make choices about their future without knowing which training programs or career paths are most likely to help them end the cycle of poverty. We heard about two primary root causes: first, funding streams typically incentivize short-term metrics (e.g., how many people participate in a training program or how quickly someone is matched with a job), rather than long-term outcomes (e.g., stability in a job, increases in wage rate over time). Second, the workforce system operates in silos, making it difficult to get a full picture of job seekers’ lives and understand who the system is serving well, and who is being left behind. An important way to begin to solve this problem is to integrate data across these silos within the workforce system. There are several national efforts already seeking to do this, including the U.S. Department of Labor’s Workforce Data Quality Initiative and Data for the American Dream Initiative. These types of efforts, once in place, will open up exciting opportunities for digital service design and tools.

Listening to users, and our gut

Our discovery work was messy—full of grey areas, hard decisions after long debates, and unexpected twists and turns. After nine months of discovery work, we took a step back to determine where we felt Code for America could have the biggest impact in the near future. While we believe technology and design can make a difference in any of these three opportunity areas, it became clear that increasing access to wraparound services was the best immediate opportunity to help people find and keep living wage jobs.

But as we closed in on our deadline for making a specific recommendation to our leadership team, we found ourselves struggling. We were frustrated with our final options in the wrap-around services space—the traditional services we were exploring had limited capacity, thereby limiting the potential scale of a technology intervention. Our team had a collective gut feeling that our users deserved better. Increasing access to cash support through the Earned Income Tax Credit had been an exciting idea early in the project, but we originally assumed that it was out of scope because few people in the workforce space knew about the opportunity or considered it within the workforce system. We hadn’t prototyped anything related to the EITC. But the EITC somehow became an informal reference point for us: “Is this as high-impact as getting people cash through the EITC? Is that?”

In the end it was not a formal process that led us to our decision—it was an honest gut check with the team. Our product manager Manya Scheps asked each of us: After everything we’ve learned about what users really need, what do we want to spend our days—and probably some long nights—working on? What did we really think would make a difference for people trying to find living wage work? The answer was clear: it was the EITC. We rushed to get a prototype up and running within a few weeks, and saw more traction than we had seen on any of our 19 other prototypes. In the end, by following the user need for flexible cash beyond the traditional workforce boundaries, we were able to identify a nontraditional but high impact opportunity.

We pitched EITC to our leadership team, and they agreed to give us more time to explore it. From January-June 2019, we prototyped three different ways that Code for America might collaborate with the workforce system to help people access the Earned Income Tax Credit. Stay tuned for an update on what we learned during our extended prototyping phase focused on increasing access to the EITC.

Acknowledgements

Our Workforce discovery process would not have been possible without the many workforce clients, staff, and leaders that shared their stories with us. We are also very grateful to the members of our Workforce Advisory Committee, who introduced us to this complex ecosystem and helped us interpret what we were learning.

Huge thanks to the many team members who supported the workforce discovery process: staff Emma Gasson, Ben Golder, Leo Mancini, Nicole Rappin, Manya Scheps, and Evonne Silva; and consultants Christina Garcia, Hannah Lee, and Jess Wainer.